“There’s more than one way to lose your life to a killer…” So runs the tagline of Zodiac, a film which opened to little fanfare outside of Fincher aficionados in 2007, yet grew to be regarded as one of the best of the decade.

I visited the set in 2006, felt the warm aura of Mark Ruffalo, the intimidating charisma of Robert Downey Jr and the general indifference of Jake Gyllenhaal, who may have justifiably been suspicious of a journalist on set, or just had more important things on his mind.

I’ve just had the pleasure of talking with Tim Coleman about the film on his fine podcast Moving Pictures Film Club – which prompted a lot of thoughts, not least that there’s a reason I’m a writer rather than a broadcaster: I need the delete key.

Another thought is how the film deals with not just frustration – it’s a maze with no exit, after all – but with the nagging suspicion that we may be wasting our time. More than fifteen years later the themes of obsession, professionalism and how you spend your life feel more painfully relevant now I’m in my mid-40s – the age David Fincher was when he made the movie.

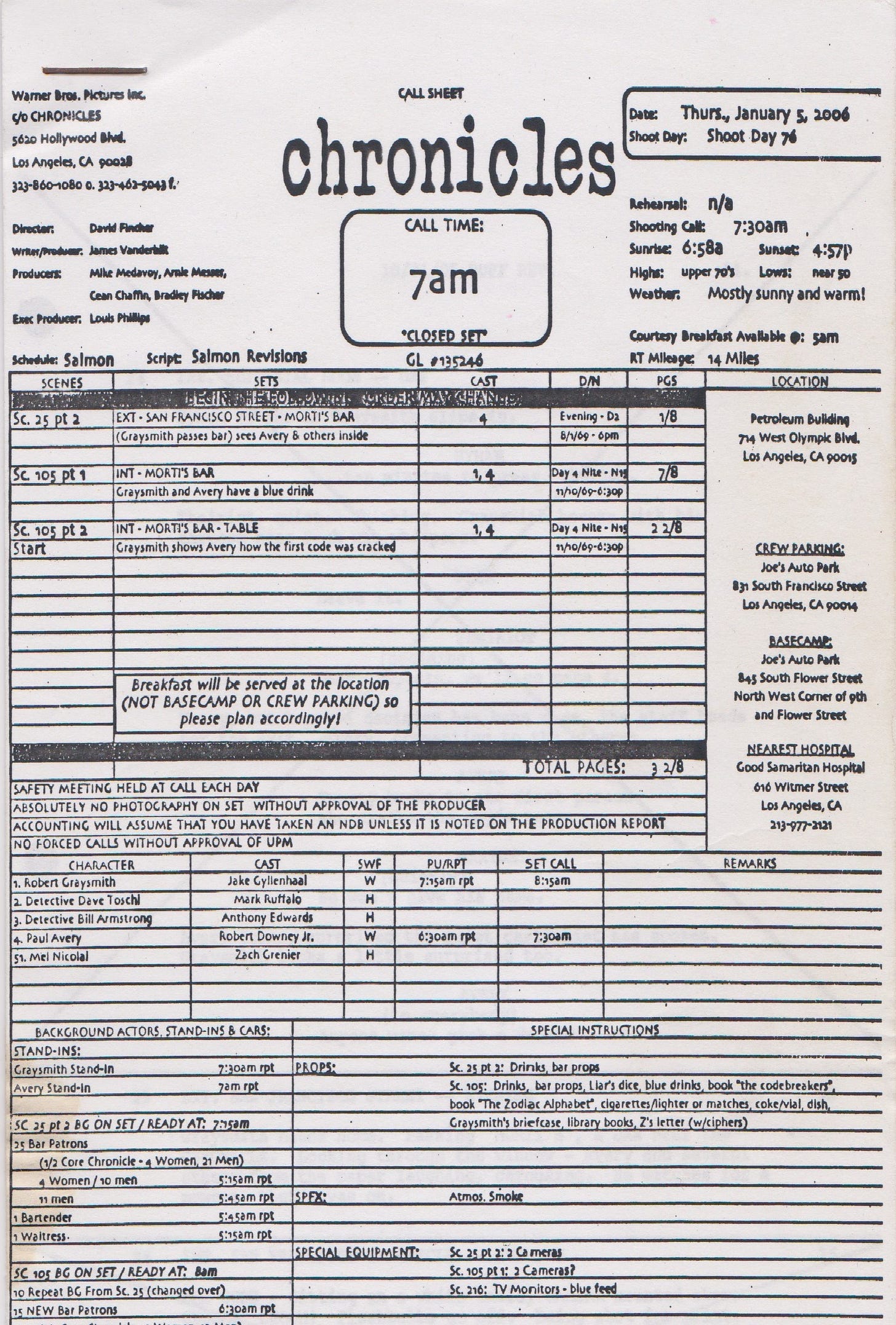

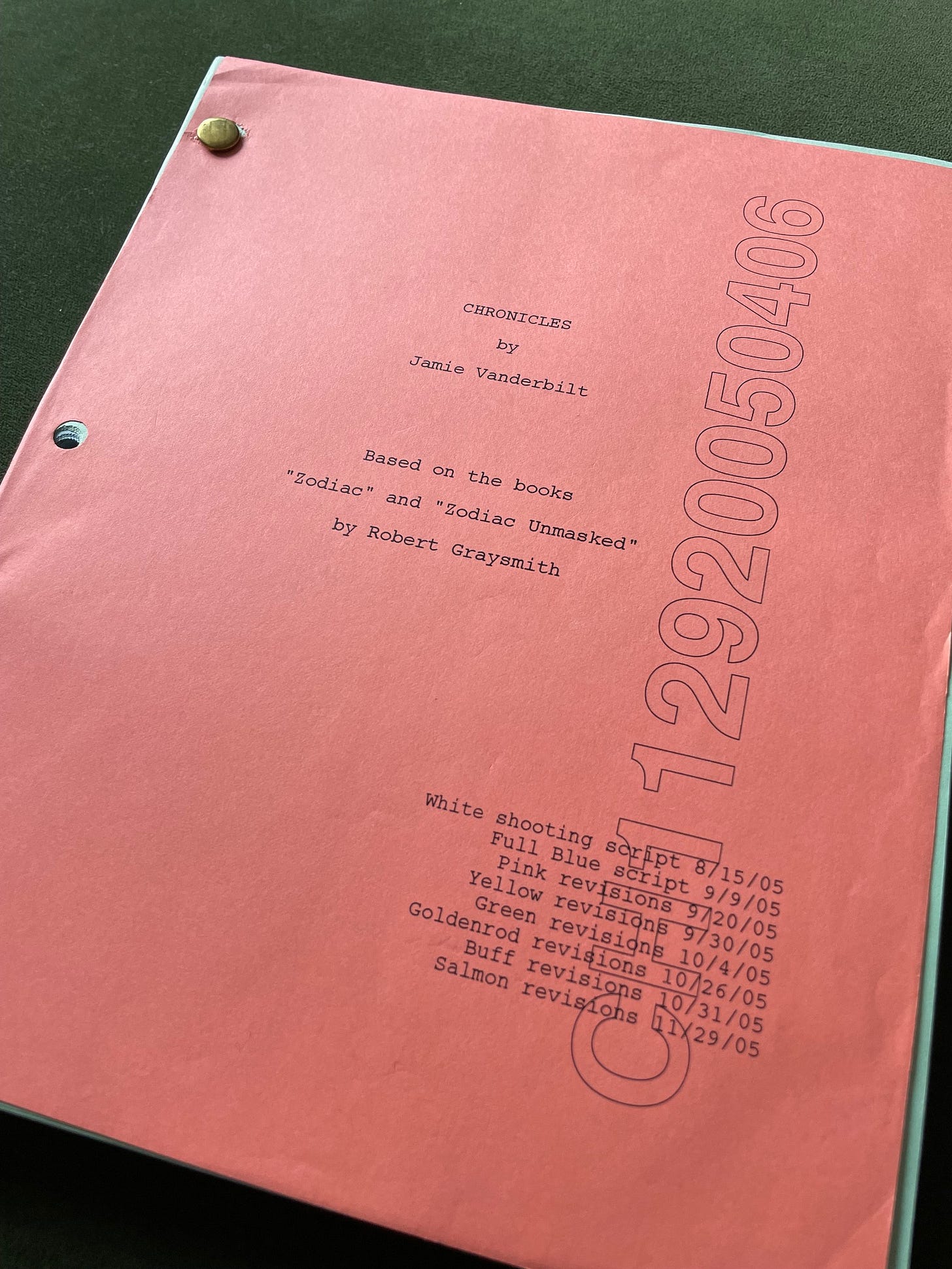

Back then, I read the doorstop script in a Los Angeles hotel, the first night of my visit (the production was dubbed Chronicles, to not scare the horses) and the next day just tried not to say anything too bloody stupid about a story I didn’t quite understand. I concentrated on keeping my phone on silent, my mouth largely shut, and being generally amazed to be witnessing Fincher at work – the first opportunity of what turned out to be many, having visited each of his productions since then, including The Killer.

I recently wrote a retrospective essay for Empire about the depth and detail and meaning of Zodiac. You’ll have to grab the back issue for that – the unwritten statute of limitations for giving stuff away free hasn’t passed yet – but the set report I did for Total Film at the time is below, or you can listen to my chat with Tim, if you want to spend a little more of that precious time.

The Devil Is In The Detail

Zodiac is the story of how an obsessed cartoonist and a dedicated cop sacrificed everything to hunt a serial killer. This is the story of how a committed director and the cast he drove crazy created the most compelling movie of 2007. Total Film follows David Fincher from script to set to edit suite for the making of a modern classic.

Originally published in Total Film magazine in April 2007.

“The guy gets two takes. If he doesn’t get it, cut his fucking arms off and leave him in the alley.”

It’s January 6, 2006.

Day 77 of the Zodiac shoot. David Fincher is a little tetchy.

A monitor plays back the latest take of Robert Downey Jr and Jake Gyllenhaal trading information in a smoky Los Angeles-standing-in- for-San Francisco bar.“This guy…” says Fincher, showing an assistant director the extra offending his eye,“…staple his feet to the floor.”

Across the floor, the actors wait for the next take. “He’s pissed,” Gyllenhaal mutters to Downey.“Can you hear him?”

Fincher tosses his headphones onto a hook and turns to face Total Film. “Hopefully one day…” He sighs.“…this will all be worth it.”

March 2, 2007. Zodiac opens in America. The poster declares “From the director of Se7en and Panic Room”, but audiences shouldn’t expect head-in-a-box shocks or a whiplash thriller. The reality is an engrossing, ’70s-set account of how a naively tenacious cartoonist (Gyllenhaal), a drunken reporter (Downey) and two polyester- clad cops (Mark Ruffalo and Anthony Edwards) tried to find a publicity-craving serial killer. The drama isn’t in the poster’s fog-shrouded image of the Golden Gate Bridge, but the pain-clouded eyes of the story’s desperate investigators. Steven Soderbergh thinks Zodiac is Fincher’s best film. James Ellroy claims it’s “one of the greatest crime movies ever made.” John Travolta’s “feeble farce” Wild Hogs (see review, page 42) beats it to Number 1 at the US box-office. So it goes.

David Fincher was seven when he first encountered the Zodiac Killer. One day, he noticed the Highway Patrol was escorting his bus home from school. He asked his dad about it. “Oh, that’s right,” said Jack Fincher, a Life magazine journalist and author. “There’s a guy who’s murdered four people and he’s sent a letter to the newspaper threatening to shoot out the tires of a school bus and kill the children on it.” Fincher laughs about this now – “I remember for the first time really wondering whether my parents were competent to take care of children…” – but the incident stayed with him.

‘HOPEFULLY ONE DAY THIS WILL ALL BE WORTH IT’ DAVID FINCHER

It persuaded him to read James Vanderbilt’s adaptation of Robert Graysmith’s bestselling books on the killings (Zodiac and Zodiac Unmasked), when his natural instinct had long been to avoid serial killer material, having made the most notorious serial killer thriller ever: Se7en.

“When he said he was interested, I was floored,” says Vanderbilt. “But he said, ‘I’ve done a serial killer movie. I’m not interested in repeating myself. I see something closer to All The President’s Men. It’s a newspaper story.’ I was like, ‘He gets it!’”

“Oh, I like that one a lot!”

David Fincher is in a good mood. He watches a scene play back with Downey Jr, who’s stood in sweaty safari jacket and sandals as hard-drinking and drug-shovelling San Francisco Chronicle reporter Paul Avery. The atmosphere is light, chit-chatty.

“What does your tattoo say?” asks Ceán Chaffin – Fincher’s whip- smart regular producer and his long-time girlfriend – indicating Downey’s ankle.

“Elias. It’s my actual last name.”

A crewmember leans into the room. “Do you need a rehearsal?”

Fincher points at Downey in disbelief. “For him to look like a drunken reveller?”

Zodiac is not a serial killer movie – it just happens to have a serial killer in it: a man who terrorised San Francisco and Northern California in the late ’60s and early ’70s and who became the most notorious multiple murderer since Jack The Ripper. Rarely have so few bodies generated so much ink. In a series of taunting, boastful letters to the San Francisco Chronicle, Zodiac claimed to have killed at least 37 people, but history records only five confirmed kills. He just had a knack for marketing. “He branded himself before he gave a name,” says Vanderbilt. “He put out his version of the Nike swoosh: the first letter was signed with just the crosshair symbol…”

The symbol would haunt San Francisco for years. But Fincher wanted to get beyond the horror and the hype to the reality of the killings – and the effect they had on those who investigated them. Zodiac producer Brad Fischer, who developed the material with Vanderbilt, recalls his first meeting with Fincher, “He said, ‘My hat’s off to you guys for taking this massive amount of information and putting it all into this 158-page document. Now let’s put the script in a drawer and go up to the Bay area and meet every single person who was involved in this investigation.’” So they did, spending 18 months interviewing witnesses, detectives and surviving victims. Fischer hired a private investigator to track down Mike Mageau, who survived being shot by the Zodiac – as recounted in the film’s chilling opening – but has since led a dislocated life, largely on the streets. When Fischer interviewed him, he was in jail in Las Vegas.

“We also met the two informants who went to the police about [prime suspect] Arthur Leigh Allen,” says Fischer. “When you sit there and look somebody in the eye and they’re telling you about this person who said he was going to write letters to the press and call himself the Zodiac Killer and shoot out the tires of a school bus and pick off the kiddies as they came bouncing out… You get a clearer sense for yourself of whether you feel he’s full of shit. And we didn’t get a feeling he was full of shit. That’s why it was important.”

‘MY FIRST DAY WAS 68 TAKES. WHEN FINCHER CAME OVER I WANTED HIM TO FIRE ME!’ - MARK RUFFALO

Everything in the script needed to be verified. Police reports were studied, urban legends were cut. The Zodiac killings crossed jurisdictions and proved a bureaucratic nightmare for the investigators. Researching the film actually highlighted evidence that had previously been ignored or forgotten, while interviewees were more receptive to Hollywood than to the law. As Fincher has it: “Making a movie is a lot friendlier than being the Department of Justice’s eighth investigator in 35 years.” Still, sitting in the edit suite, halfway through the shoot, Fincher is musing: “I don’t know how many people are going to believe that what we’re telling them is true…”

On screen, a pretty girl is lying by the picturesque Lake Berryessa, being stabbed to death. She sobs. She screams. A hooded man knifes her repeatedly. “She was good, man,” reflects Fincher, of Pell James, who played Cecelia Shepard, Zodiac’s fourth murder victim. “She was so game. My God. We did 35 takes of that stabbing because we just couldn’t get the piece to look like he was actually stabbing her. So we shot 35 takes and then we went back the next week and shot 30 more. She was black and blue. She got it, though.”

Fincher talks about Funny Games, Michael Haneke’s ruthless anti-thriller. An upsetting exploration of everyday violence, it’s clearly a reference point for the eerily straightforward murders in Zodiac. “I want it to be simple,” says Fincher. “Here it is: it’s right here. A guy comes in and goes, ‘I’m going to tie you up. Get on your stomach.’ And all of a sudden, you’re just fucked.” Bryan Hartnell, who survived the Berryessa attack, was consulted for the scene. Fincher is a little concerned about how he’ll react to a joke – about his studies – which they’ve put into the dialogue. There’s clearly a tension between dotting every ‘i’ and entertaining an audience (as it turns out, Hartnell will be more than satisfied with the finished picture). “It’s walking the line,” says Fincher. “Ken Narlow [a detective involved in the Zodiac case] was there on the day we shot the stabbings. As soon as they walked out the trailer, he burst into tears and couldn’t watch. He just said, ‘They look so much like them and I forgot how young they were – oh my God.’”

Fincher feels a sense of responsibility to that. It’s one Hollywood has not always felt. Back in 1971, Dirty Harry riffed on the real-life killings (with Zodiac cunningly renamed ‘Scorpio’), even as the killer was still sending teasing letters to the Chronicle. “People were in fear. It was upsetting, the letters and the taunting,” says Fincher. “Then Dirty Harry sort of used Zodiac as a jumping off point… There’s a big moment in Zodiac where the police department watch it and kind of go, ‘Wow’. And all those guys cooperated with that movie. I’m sure Dave Toschi [the detective played by Ruffalo] met with Clint Eastwood. He certainly met with Steve McQueen [for Bullitt].”Nonetheless, Eastwood – a revered figure at Warner Bros, who co-financed Zodiac with Paramount – is notable by his absence from the Dirty Harry footage shown in Fincher’s film. “He didn’t want to be in a serial killer movie,” says the director, with weariness but no recrimination. “I guess he’s done enough of them.”

Harris Savides, the cinematographer, has made final adjustments to the scene lighting.

“I like it,” says Fincher. “It feels real.”

Gyllenhaal wanders over and puts his arm around Savides.“Watch out,” says Fincher. “You’ll get a hug.”

A Starbucks run arrives. The production assistant makes sure Fincher has decaf.“ They don’t want to get me hopped up!”

Downey and Gyllenhaal sit on the bar stools, ready for action. Take one…

Downey: “What’s that drink you’re drinking? That’s my real question to you.”

The script supervisor turns to Fincher: “Did you like that line he added?”

“No. I hate it when he does that.” Take two, take three, take four…

Gyllenhaal: “It’s called a Blue Alga. It’s redundant, but it’s good.” Fincher calls across: “Speaking of redundancy…”

Take five, take six, take seven, take eight, take nine, take 10… “Last one,” promises Fincher.

“What does that mean?” Savides asks the script supervisor. “It means there’s five more,” she says. There are actually two more takes.

In the edit suite, the Berryessa sequence ends and another scene flickers across the wall-mounted monitor: Gyllenhaal as Chronicle cartoonist Robert Graysmith, walking across the newspaper offices to where the staff has gathered to read another letter from the killer. Fincher wants to know if it looks ‘period’. He’s concerned to avoid kitsch. “I didn’t want to make a movie about sideburns; I didn’t want to make a movie about plaid and flared pants, bell bottoms and platform shoes.”

He hasn’t. Stylistically the film will be considered a departure for Fincher: the MTV auteur, famous/notorious for his envelope- pushing camerawork and supposedly in-your- face aesthetic. Visually, it’s relatively simple: two shots, few cuts, stable camera. Some reviewers will say this is the director maturing. They’ll be wrong. He’s just using the right tools for the job. The frame-rattling visual virtuosity of Fight Club matched the anarchy and aggression of Tyler Durden. The elaborate, digitally enhanced track through Panic Room’s house established the geography of the claustrophobic thriller (and, alright, maybe there was a little bit of showing off). And in Zodiac, the camera’s steady, matter- of-fact focus on people is because that is where the story lies. As ever, Fincher uses CGI and whizz-bang visuals only when it’s necessary – as in a key scene when dogged detectives Toschi and Bill Armstrong (Edwards) walk through the Chronicle offices and digitally generated symbols from the killer’s coded messages – hang in the air. A passing of time, growing obsession and a sense of panic are all deftly conveyed in a few seconds. It’s superbly economical storytelling (though it cost thousands of dollars). “He could have shot the shit out of this thing,” says Vanderbilt. “And I think the reason he didn’t is not because he’s ‘matured’, but because he’s a great storyteller and he just wants to serve the story. And that’s why he’s such a joy to work for.”

A joy for the screenwriter, then, and the producers – but a Fincher gig is never easy on the actors… “My first day was 68 takes with Jake and I was like, ‘Please kill me’,” says Mark Ruffalo, whose nuanced, subtle turn as worn-down cop Toschi is the stand-out in an impressive ensemble. “When Fincher came walking over at one point I was like, ‘I hope he’s coming here to fire me.’ Then I realised it had nothing to do with Jake and I... Well, maybe the last 30 takes were us, but it was a huge dolly crane shot with 30 extras, five pages of dialogue and a really intense scene... So there were a lot of things in play. It doesn’t mean he doesn’t respect the actors and their processes, but he does want people to be the best he believes they can be. Sometimes with ‘movie stars’, we want to come in and be a little lazy and do our ‘good enough’ and go home… [but] I know what David’s set up is. He’s taking a stab at immortality – he knows that. Somewhere along the way I think Fincher said to himself, ‘Good enough is not fucking good enough.’”

“He’s kind of a sweet guy,” says Downey Jr. “But then you’re on the set and he knows more than most directors and more than is probably appropriate. So he’s just... I hate to say ‘right’…”

Robert Downey Jr is on fire. The resurgent actor has been smoking nicotine-free cigarettes throughout his latest scene. But, for reasons best known to himself, he’s been stubbing the butts out in tissue paper – which has finally ignited, underneath Gyllenhaal’s seat. There’s much laughter.

Fincher walks past and Downey offers an exaggerated flinch… The scene resets. Fincher disappears to the monitor and calls

across: “Last one.”

“Yeah, right,” says Gyllenhaal.

“Have a little faith,” says a crewmember.

“Come on!” says Gyllenhaal.“We’re going to fuck all night!”

At lunch, he looks tired.

“I don’t want to satisfy that part of David that enjoys having people hear that it’s not easy,” he says, of the repeated takes. “But it gets tedious. It really does... It can be pretty intense.”

October 17, 2006. Fincher is considering his actors, the difficulty of managing performances and personalities. “The alchemy of it is so complex,” he muses. “You know, it’s easy to like people for two hours… It’s hard to like people for 120 days. They do kind of get on your nerves.”

He isn’t referring to anyone specific. But it’s obvious from being on set that some actors find it frustrating: the marathon of capturing the mini moments that correspond to the movie in Fincher’s head.

‘THERE’S A PART OF FINCHER THAT ENJOYS HAVING PEOPLE HEAR IT’S NOT EASY’ - JAKE GYLLENHAAL

“You know, Downey likes to play, but he likes to know there’s light at the end of the tunnel.” And how did Gyllenhaal cope? “I can tell you I don’t think he had a real good time,” says Fincher, who cast him on the basis of Donnie Darko. “But I can also tell you that I still sleep at night…” He leans back at his desk. Face deadpan.

On the wall there’s a painting of waves crashing against a beach, with a motto of sorts inscribed across it: ‘PITILESS PURITY DUDE.’ His office is clean; hard-edged and functional. There’s a couch, but it doesn’t look slept on. There are books of photography on the coffee table, but they don’t look read. Work goes on here. On the desk are notes from Fischer, Vanderbilt and Warner Bros about the latest cut of Zodiac. The final version is yet to be locked down and Fincher will continue to tweak and trim for a few weeks, even as he starts shooting his next collaboration with Brad Pitt, ambitious F Scott Fitzgerald adaptation The Curious Case Of Benjamin Button. (The leaner cut will prove less artful in places, but arguably more arresting.)

For now, he’s considering how to market the movie. Ironically, given Zodiac was a master of self-publicity, it’s proving difficult. He glances briefly at the poster, propped against the wall. “Obviously there’s no way they’re going to put a poster up which doesn’t talk about Se7en,” he says. “But my point is, ‘If you want bad word of mouth, you’ll make people think this is Se7en…’” Fincher is fascinated by the idea that the Zodiac’s compulsion, ultimately, wasn’t killing, but communicating with the Chronicle. “That became far more gratifying and seductive than what he started out doing…” So, he was an attention seeker: surely a trait a director can identify with. It may be the basest reason – behind the exploration of ideas, the interest in human behaviour – Fincher directs. “Look,” he says. “There are times when you’re [in a screening] ready to throw up and 1,500 people all laugh at a joke you worked so hard to get right or they all gasp. It’s pretty great you can make that happen. It’s the trained dog in every director that, you know, has that need and wants to do a back-flip and see everybody clap.”

A sort of pathological need to be liked?

“I’m not that hooked on being liked!” He laughs. “But I enjoy being able to manipulate, being able to elicit... I think that’s fun.”

Marketing, it’s fair to say, is less so. Zodiac’s imposing-but-chilly one-sheet campaign doesn’t present it as an intriguing cold case or give it a human face and Fincher is going back and forth with the studio to ensure the trailer “doesn’t insinuate it’s The Grudge or something…”

He speaks with a mix of incredulity and faint amusement. For the director who survived Alien3 and the marketing battles of Fight Club, this is a mere skirmish. The important thing is finishing the movie. “Films aren’t finished,” he notes. “They’re abandoned.” So, was it worth it? “I won’t know,” he says. “I won’t know for 10 years.”