Going back in time to watch the filming of The Curious Case Of Benjamin Button

A set visit, shocks and discovering there's no time like the present...

Nothing else that is so certain is as surprising as age. This first struck me a few years ago when my eldest child turned 18 and, with spectacular solipsism, I thought: ‘Hang on, if my son is a man then that must mean I’m old.’ None of my own birthdays had hit so hard.

When I was a boy I used to believe – to hope, really – that one day I would, like Tom Hanks in Big, wake up and look in the mirror and find myself a fully formed adult, maybe with a caption saying, ‘10 years later’. Then you realise this is not a hope but basically a reality, as it’s a blink and you’re there (except I’d kill to have Hanks’ abs). As Jose Mourinho told Dele Alli, “I am 56 now and yesterday, yesterday, I was 20.”

I’m clinging to my mid-40s and realising the truth of this, as well as the reality that we’re never really adults – even our parents are not adults. Everyone is busking it. We never really feel grown up. As Martin Amis told Jude Rogers for Word magazine, in a quote she posted upon his death last year, “We’re like children all our lives, because every 10 years we have to acquaint ourselves with a new set of rules.”

The Curious Case Of Benjamin Button deals with all of this, in a fantastical Hollywood romance, and at the time – certainly in my peer group – there was some confusion that David Fincher was interested in the heart rather than another head in the box. The film was grand, sweeping, and sad. Where was the bloodshed?

I visited the set in New Orleans around Valentine’s Day 2007, relieved that my first Fincher production report, for Zodiac, hadn’t made everyone decide having this journalist around was a terrible, terrible error. Below is my initial piece for Total Film magazine, then the follow up for Empire. I moved jobs, partly out of ambition, partly out of a desperate desire to save my floundering marriage (the theory being more time at home would help).

A couple of memories from the set now stick out. One was hearing a cockney accent and turning to see Jason Flemyng, thinking, “How is the bloke from Snatch in this?” Flemyng would turn out to be terrific, both on screen and in person. As two Brits, equally surprised to find ourselves on a Fincher set, we went out on the town, seeing a jazz hip hop combo and ending the night with his promise that if I ever wanted to cast him, he’d be there (a promise he honoured, a blink and seven years later, when he starred in my short Bricks).

The other memory is of sitting with Fincher in a production office, reflecting on family. bemoaning not having been around much for my son when he was little. This elicited a bemused look and a question: “How old is he?” He was five. Fincher raised an eyebrow: “I have to tell you, he’s still little.” I nodded and smiled and of course ignored this, not realising that 17 years later I’d give almost anything to go back and hug that little five year old and tell him that the grumpy man who would take him to school weighed down by work worries and a hangover, loved him more than he could ever, ever express and was, really, honestly, just trying his best, and you are absolutely enough. But. Time goes by.

I’ve been fortunate enough to become friends with Button’s screenwriter, Eric Roth – a wise and wistful man who has forgotten more about life (and writing) than most of us will ever learn – and you see a lot of him in the film, as well as Fincher (though, naturally, him being a screenwriter it seems we never interviewed him at the time). Every few years I re-watch the film and am struck by its craft and ambition and the understated majesty of Pitt, but as it goes on I think, ‘I’m not terribly moved, perhaps I was too soft’ and then Benjamin writes to his daughter and then reflects on those he’s known… and I am undone, a snotty, teary mess, weeping… like a child.

History In The Making

No decapitations, rage or brutality… is The Curious Case of Benjamin Button really a David Fincher film? You bet: it’s his magnum opus. In a world exclusive, Total Film visits Fincher’s set to witness the making of a modern American classic...

Originally published in the Christmas 2008 issue of Total Film.

Wrapped in a voluminous white blanket, and partly crammed into one of the cribs, there sat an old man apparently about 70 years of age. His sparse hair was almost white, and from his chin dripped a long smoke-coloured beard, which waved absurdly back and forth, fanned by the breeze coming in at the window. He looked up at Mr Button with dim, faded eyes in which lurked a puzzled question… [He] suddenly spoke in a cracked and ancient voice. “Are you my father?” - The Curious Case of Benjamin Button, By F Scott Fitzgerald

“You could say there’s death… Death is the core of everything… of all my movies.” David Fincher is having a haircut. He’s in a trailer, taking a trim between set-ups on his seventh film, The Curious Case Of Benjamin Button. He’s chatting about grandchildren with the woman wielding the scissors, who has a family photo on the dresser. “He’s a black belt?” says Fincher, peering at the boy in the picture, with surprise. “He can kill with either hand! It’s going to be hard to discipline that child…”

Between snips and quips, Fincher is discussing the themes of his movies; to a point. He does, he says, “try not to think about that stuff… I like so few things; I don’t want to limit myself by going, ‘Oh, that’s the thing you always like!’” The Flaming Lips are on the radio. “Do you realise…” comes Wayne Coyne’s distinctly fragile voice from the tinny speakers. “That everyone you know… someday… will die…”

Fincher has distinct tastes. The New York Times once wrote an article questioning why he and his peers – Spike Jonze, David O Russell, Kimberley Peirce – weren’t more prolific. He has a simple answer: “It’s too hard, man.” Spider-Man, Mission: Impossible III, Seared, Squids, They Fought Alone, Lords Of Dogtown, The Black Dahlia: the 46-year-old Denver-born director has been linked with each – some went on to be made by others, some still fester in Development Hell. If there’s one thing Fincher learnt from Alien³ – easily the worst experience of his professional life – it’s to go into production with your eyes wide open. “I try not to be a guy looking for a gig, because that puts you at a disadvantage,” says Fincher. “Joel Schumacher once told me, ‘Never care more than they do.’ and I think that’s wise. I think you go into it and say, ‘This is what I need’. Tell the truth…”

The truth nearly scuppered The Curious Case Of Benjamin Button. An adaptation of an F Scott Fitzgerald short story from 1922, it’s been knocking about as a potential movie since the early ’90s, touted variously as the next gig of Spielberg, Jonze and Ron Howard, whose version was kiboshed because of a spiralling budget. In 2005, as Fincher was poised to shoot, cash concerns saw it shut down once again. “But then we made Zodiac with them [Paramount and Warner Bros] and we gained a trust that if we said it was going to cost ‘X’, it wasn’t going to cost ‘X’ times two. So the planets aligned, Cate Blanchett was available and Brad had a baby and decided he liked the script and here we are.”

“YOU ARE AN EVIL, VILE AND SICK MAN,” HE SAYS.

“AND THAT’S WHY YOU ARE CONTINUALLY WORKING FOR ME…”

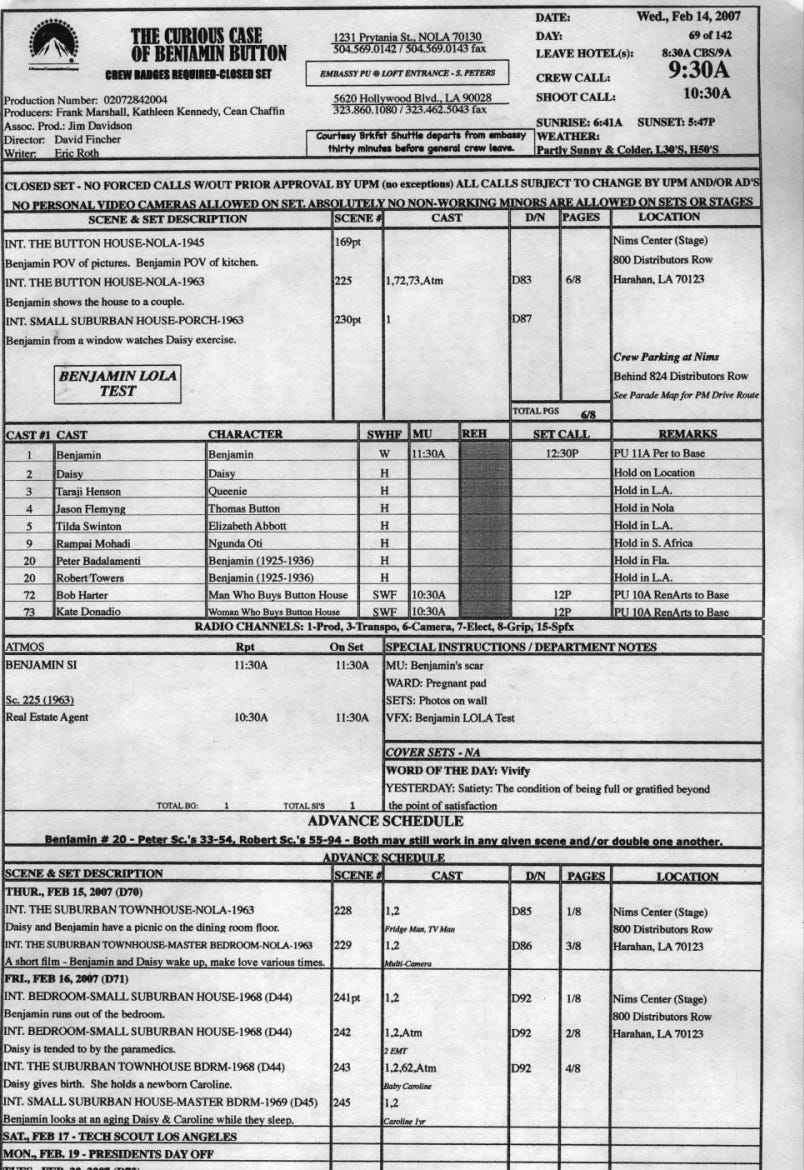

“Here” is New Orleans, Louisiana. Day 69 of the shoot, 14 February, 2007. The crew members greet each other with “Happy Valentine’s Day” – Cupid’s annual knees-up is more of an event in America. Later, we all enjoy celebratory champagne (from plastic cups), courtesy of Brad Pitt. In the morning, a glance at the call sheet shows a scant three set-ups: ‘Benjamin POV of pictures/Benjamin POV of kitchen,’ ‘Benjamin shows the house to a couple’ and ‘Benjamin from a window watches Daisy exercise’. This will probably amount to only about 20 seconds of film. Shooting it, somehow, will take 11 hours. The material may appear to be a departure for Fincher, but his methods remain the same: exhaustive, exacting. The first set-up is a tracking shot, down a hallway festooned with family pictures. Around the fifth pass, Fincher mutters, “Not bad.” “Not bad?” says Kim Marks, the camera operator. “Don’t you know the word ‘excellent’?” There is no pause: “No.”

As with Zodiac, Fincher is shooting tapeless, with images captured straight to digital hard drives. At lunch, he reviews the morning’s footage on his laptop – logging into a website where dailies have been uploaded. Using PIX (Project Information Exchange), he then makes notes for the editor and cinematographer. Fincher uses three preset buttons: ‘Could be better’, ‘Performance good’ and ‘Excellent’. You imagine the first is used quite a lot. Happy – or at least, mildly content – with the footage he has seen, Fincher then turns his attention to some streamed auditions, as he’s casting for later in the film’s 150-day shoot.

As a particularly nubile actress appears on the screen, one of the crew leans in and makes a lewd comment. Fincher turns. “You are an evil, vile and sick man,” he says. “And that’s why you are continually working for me…”

Evil, vile, sick, fascistic. Fincher’s films have been called a lot of disparaging things. He is cinema’s ‘Prince of Darkness’: the man who torched Sigourney, put Gwyneth’s head in a box and threw Michael off a roof. He beat Jared beyond recognition, incarcerated Jodie in a vault and made Jake teeter on the edge of a nervous breakdown. Fincher is unflinching in his desire to make us flinch.

Perhaps he is aware of his reputation. There’s probably even a part of him that enjoys it. And yet, The Curious Case Of Benjamin Button is – at least in part – a romance, scripted by Forrest Gump scriptwriter Eric Roth. He calls it “a fable. It’s about a man who ages backwards and whatever that means in one’s life. And if you have parents or children then I think you’ll probably like it. It’s about life and death.” One thing’s for sure – it’s definitely not Ei8ht…

Fincher had always been interested in the project, but its appeal crystallized after the death of his father – Jack Fincher, journalist and writer – in 2002. The director started to think about the difficulty of dealing with death, as much for those left behind as those who go through it; about the toll of loving someone.

“I thought the movie was kind of an exploration of the duty that love is,” he says. “I mean, it sounds unpalatable, the way I’m saying it, but it was wrapped in a tender filo, a nice pastry. The upshot of it was about a guy who grows up in an old folks’ home, sees people die all around him and so is sort of comfortable with that passing, falls in love… is… you know… it doesn’t happen… boy meets girl, boy gets girl and whatever after that… I just thought…” He pauses. “I just thought it would make a rippin’ yarn!”

“Good Lord!” he said aloud. The process was continuing. There was no doubt of it – he looked now like a man of 30. Instead of being delighted, he was uneasy – he was growing younger.

He had hitherto hoped that once he reached a bodily age equivalent to his age in years, the grotesque phenomenon which had marked his birth would cease to function. He shuddered. His destiny seemed to him awful, incredible.

- The Curious Case of Benjamin Button, By F Scott Fitzgerald

At lunch, the day before Valentine’s, Fincher shows Total Film another scene on his laptop. Cate Blanchett is Daisy, Benjamin’s lover. She’s in a swimming pool. She finishes a length and looks up to Benjamin, standing on the tiles. She looks troubled, upset. Because, says Fincher, as she’s getting older, he’s getting younger “and, ironically, looking like Brad Pitt.” The story is about love separated by time – as Blanchett has it, “There’s a moment in time when we’re together, like star-crossed lovers.” Benjamin, born circa 1918, lives through WW2, the swinging ’60s and beyond, almost to the present day. It could be The Curious Case Of The 20th Century.

Pitt had to be convinced to sign up. At first unsure, he re-read the script after the birth of his first child and called Fincher to ask what he’d done to the ending. The answer: “Nothing, man. You just had a baby!” Paternity, mortality… Time changes everything.

Total Film witnessed the birth of Benjamin earlier in the week, seeing his father Thomas (Jason Flemyng) discover the nature of the new arrival and do a runner, ditching the baby in the New Orleans night. It was a day off for Pitt, who was probably grateful of the break, given days where he plays the older-looking Benjamin require 4am starts to apply extensive make-up. But today he is aged. He has grey hair and grandpa glasses. He’s filming in the Button townhouse, walking down the hallway, looking at the pictures. The star and director – working on their third film together – clearly have an understanding. “You need to ease into those stops,” Fincher tells Pitt, “as if you were retarded.” Another take. Pitt nails it. He’s a convincing pensioner. Not that all the aging effects are in-camera: one of the key reasons the film has taken so long to mount is the demands it places on CGI.

“We had to figure out a way [to age Benjamin], aside from casting six different actors to play the same person, so we did tests and were able to cast separate bodies and do head replacement and put this CG character on the shoulders of the body,” says Fincher. “We didn’t want it to be animated, we didn’t want it to be: ‘Here’s Gollum, from the clavicles up!’ We had to make it so that Brad was driving the performance. So we worked out a way to do it.” He pauses and gives a smile. “It still hasn’t actually worked satisfactorily, but we have every reason to believe it will…”

Wry as he is, Fincher will make it happen. The work-in-progress images we see are startling. He shows us Blanchett, before and after CG rejuvenation. “That’s Cate as she looks today – see that stuff [he uses the cursor to show a minor skin blemish], those little imperfections of which she has maybe two – and this is her at 21.” As she ages and Pitt grows younger, virtually every frame will be retouched. The special effect is showing the passing of time.

“MY FAVOURITE THINGS I’VE BEEN INVOLVED WITH… THERE WERE A LOT OF THINGS THAT WERE DONE IN SPITE OF MY INSTINCTS…”

Back on Valentine’s Day, haircut finished, Fincher is walking back to the stage. Is this a departure for him? Maybe. We discuss the theory of one critic, that his previous films, up to Zodiac, all had lead characters in conflict with “the doppelgänger of the protagonist”. Except for The Game – his “least convincing” picture. “Hmmmm,” says Fincher. “There you have it: ‘The reason that didn’t work was because he wasn’t making that same old movie.’” He pauses. “My favourite things I’ve been involved with, there are a lot of reasons outside my own influence why I like them. There were a lot of things that were done in spite of my instincts, which now make them memorable to me! That’s why it’s such a bizarre art form to deal with, because you’re… it’s an instinctual thing, you’re looking for somebody’s instinctual response to the day’s work and the story and yet you’re going to have good days and bad days.” He pauses again. “You’re going to have a lot of bad days…”

We arrive back at the shooting stage. It’s empty. Fincher does a comedy double-take. “Is everybody at fuckin’ lunch or something?” He lets out an exaggerated sigh, “You can’t leave for 10 minutes…”

Scroll on for the edit suite piece from Empire…

The Curious Case of Benjamin Button

Romance, death and director David Fincher – it’s a time twisted love affair...

Originally published in the November 2008 issue of Empire magazine.

“There are moments in this movie a hair’s breadth shy of cliché, but they’re completely re-invented by having someone in the scene who is 12 years old, but looks 7.”

David Fincher is not wrong. Empire is sitting in his Hollywood office, having just seen 27 minutes of scenes from The Curious Case Of Benjamin Button. It looks - let's get the embarrassingly OTT adjectives out of the way early - beautiful, affecting, entrancing. The pitch is peculiar, no doubt: baby Benjamin is born elderly and grows younger. Abandoned at a nursing home, the wrinkle-wracked infant is introduced to the residents. “Oh my Lord,” says one. “He looks just like my ex-husband!” Another clip sees him being prayed for at a revival meeting. The minister asks this ‘boy’ in a curdled, invalid body what age he is. “Seven, but I look a lot older.” Then there's the delicate dinner date where Benjamin (Brad Pitt, looking pensionable) takes his first taste of caviar - and of a kiss - with Elizabeth (Tilda Swinton).

She is handsome, on her way to being distinguished, eyes tinted with regret. He is bewildered, peepers holding innocence and hope, with a prune’s complexion. Their relationship may be his first, but the picture pivots on his love for Daisy (Cate Blanchett), a childhood friend who grows older while he rejuvenates. “It’s amazing how it changes the terrain,” says Fincher. “It was sort of an interesting way of repurposing the grand Hollywood romance.”

‘Romance’ and ‘Fincher’ are not words often used in proximity. Until Zodiac, he was the MTV auteur whose urban Gothic thrillers were considered in-yer-face and none-more-modern. Even his meticulous recreation of the investigation into the notorious Californian serial killer featured, well, a serial killer. This wouldn’t, you imagine, make him the immediate go-to guy for a fable from the writer of Forrest Gump - a project once linked to Ron Howard. But Fincher first read a Benjamin Button script - based on the F. Scott Fitzgerald short story - back in 1992, and when a new draft by Eric Roth landed on his desk in the early Noughties, he was still attracted to the material. “I don’t think (producers) Kathy (Kennedy) and Frank (Marshall) were shocked or dismayed that I was interested, but I think they were curious as to what my take on it was...”

“THE SPECTRE OF DEATH DETERMINES THE YARDSTICK

BY WHICH YOUR LIFE IS MEASURED.”

Fincher’s take was informed by changes in his own life since he read the original script: first becoming a father, then the death of his own. “One of the things the movie’s about, very profoundly, is death,” he says. “When my father died... [l saw] that fear, that thing which comes with going, ‘Wow, maybe this morning’s breakfast was the last.’ It’s a profound thing, just the way it makes you feel...” He pauses; considers. “I think I probably read Robin Swicord’s draft and thought it was about love. And then I read Eric Roth’s and thought it was about death. And I thought that was a more profound context for a love story. You know, the greatest love stories always end in death. The spectre of death determines the yardstick by which your life is measured.”

The Curious Case Of Benjamin Button deals with big themes, then. Though the biggest issue for the production was a technical one: “Yeah, ‘How do we do it? Does it just involve gluing rubber all over his face?’ Which was - more often than not - the solution!” Fincher laughs. He’s deep into post-production, dealing with the picture’s most challenging aspect, on several levels: time. With a story spanning the 20th century, Pitt had to gain – and lose - decades, going from pensioner to prepubescent. It obviously couldn’t all be achieved with make-up. “Let me show you,” says Fincher, clicking away at his Mac. A green-faced Pitt appears on the monitor, the computer-generated elderly version of his visage on the right of the screen - aping his actions. The effect is extraordinary. If Angelina Jolie wants to know how her fella will age, here’s the answer.

It’s groundbreaking performance-capture, with Pitt acting Benjamin at every stage of his life - from elder to infant - his face then digitally altered and put into scenes where body actors - wearing blue masks - have interacted with the other performers. “So then we could go make the movie in whatever way we wanted to,” says Fincher, “and just put the head on later. All the acting stuff you see is Brad looking on a monitor and reacting to it. Then we put his face on...” It sounds simple. It’s not.

The shot Empire is looking at is dated January 18, 2008. Principal photography wrapped in May, 2007. It took months of intensive work, after millions upon millions of dollars had been spent, before Fincher could know, for certain, the CGI would convince.” We knew there was going to be stuff that was just going to be horrifically embarrassing until it was... tolerable,” he says, of the effects. “But the most important thing in defining anything is defining the things you are not going to do. There are certain shots you just can’t do with this. But I will say that the visual effects supervisor, Eric Barba, who I love, I joke with him all the time: as soon as he tells me, ‘You can’t do this!’, that’s when I go, ‘Sit the fuck down. Shut the fuck up. That is reason enough to do it!’

“There’s one scene where the (motion capture) actor who plays Benjamin puts on his glasses, with this blue Spider-Man mask over his face, and the guys from (effects house) Digital Domain go, ‘No, no, you can’t!’ I was like, ‘Look: you figure it out. Because I think you can...’ And it’s one of those scenes where your subconscious, your lizard brain, goes, ‘That’s real!’ That one little action and the way his pupils focus... You just go, ‘What the fuck is going on?”‘

Fincher smiles, proud of the achievement. Still, halfway through production, he must have been a little concerned. “Yeah. You’re saying (loudly), ‘Guys, don’t worry: this is going to be fine!’ (Whispers) ‘Jesus Christ, I hope this works...”